“STEINHOLT” – Photographs By Christopher Taylor

“STEINHOLT”

Photographs By Christopher Taylor

A cura di M O N I C A D E M A T T E

Inaugurazione: 2016 / 04 / 09/ 15:00

Durata: 2016/04/09 – 2016/08/08

Dove:Mo Art Space

Marks in Time

Steinholt is the third series of photographs that Christopher Taylor has dedicated to Iceland, the homeland of his wife, Alfheidur. The first series was entitled From Under the Glacier (1996 -1998), in honor of the book Christianity at Glacier (1972) by Halldor Laxness, while the second was devoted to the Westman Islands (Vestmannaeyjar, 2006-2010) from where Alfheidur’s mother originates.

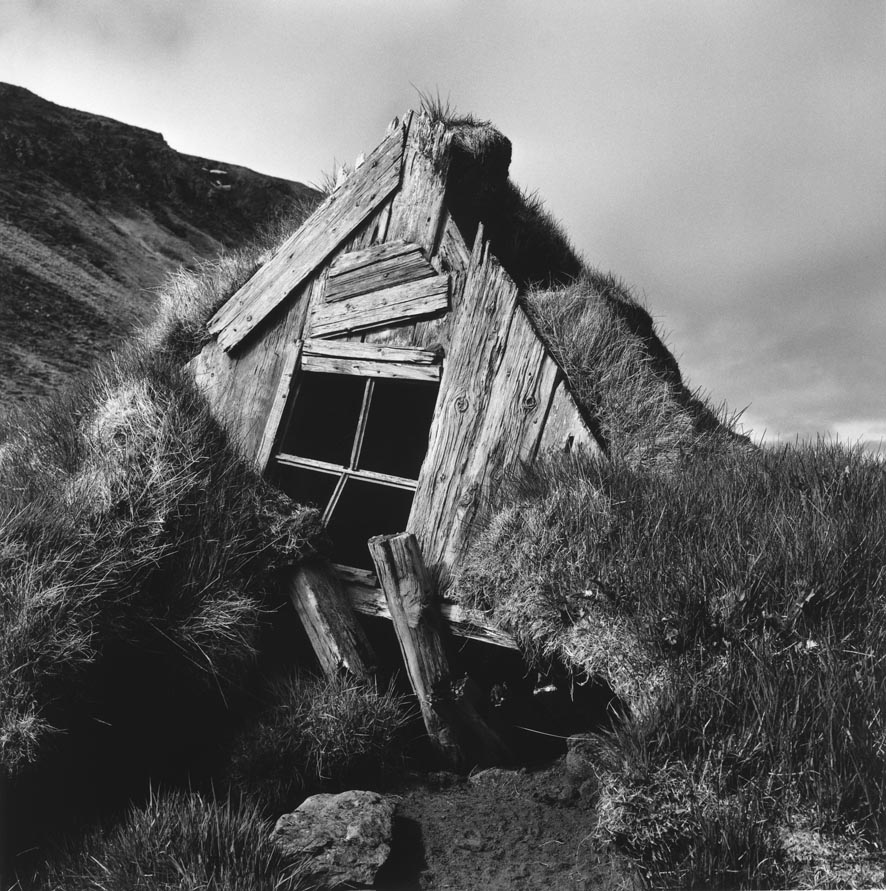

Christopher’s relationship with nature and human life in Iceland has deepened since he and Alfheidur acquired Steinholt, a modest house built by Alfheidur’s paternal grandparents in Thorshofn, a small town located on the country’s north-eastern coast. Since then, Christopher has spent every summer in the tiny coastal village, home to around 300 people. Here he has devoted himself to restoring the house, working for a fish processing plant, and, above all, exploring the local terrain in long, arduous hikes, weather permitting. No longer merely a transient guest, struck and fascinated, by the indomitable grandeur of the country’s natural environment; or hostage to enclosed spaces during spells of bad weather, nowadays Christopher shares part of his life with the villagers of Thorshofn. He makes the time he spends there meaningful by interpreting the surrounding landscape and observing the traces left behind by those who have perished or moved on, still remembered by people who remain.

The stories Christopher has managed to collect, both through oral accounts and by drawing on the collective memories recorded in the 1940’s by itinerant schoolteacher, Benjamin Sigvaldsson, have struck and moved Christopher through their simplicity and harshness. They are the experiences of men and women whose sole activity and preoccupation had been that of managing to survive in a forbiddingly inhospitable setting. Raisers of a few scanty sheep, fishers when the sea allows it, in a country where the wind and cold mean that even the trees show stunted growth; these people have been the sometimes-heroic protagonists of almost intolerable situations. Sometimes unable to make a living off the isolated farms in which they were born, they were forced to leave and start anew elsewhere. Others suffered abuse, while yet some demonstrated courage and resolve under the most adverse circumstances; all of them painstakingly survived by gleaning what little they could from the surrounding environment.

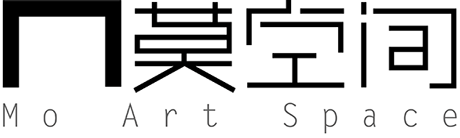

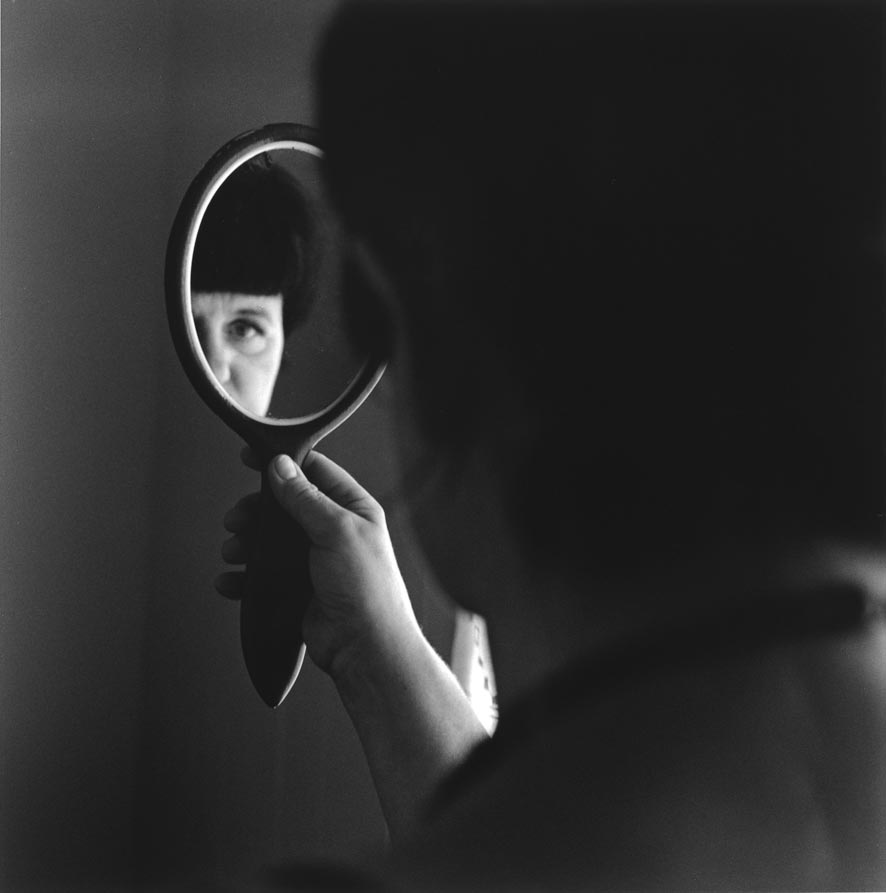

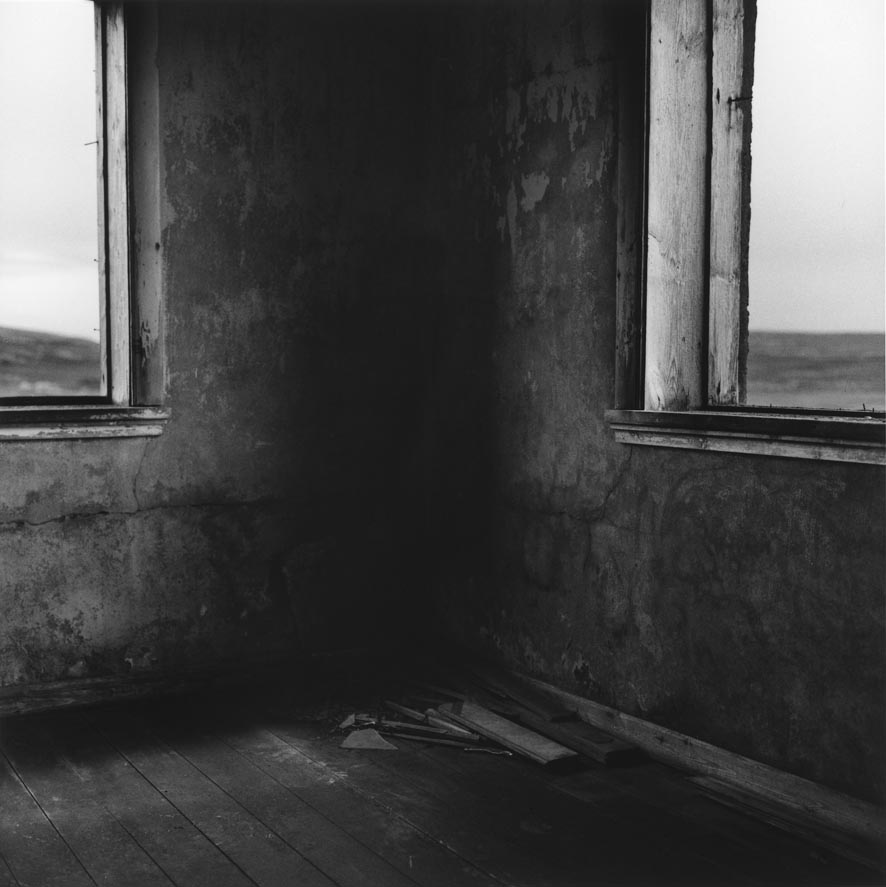

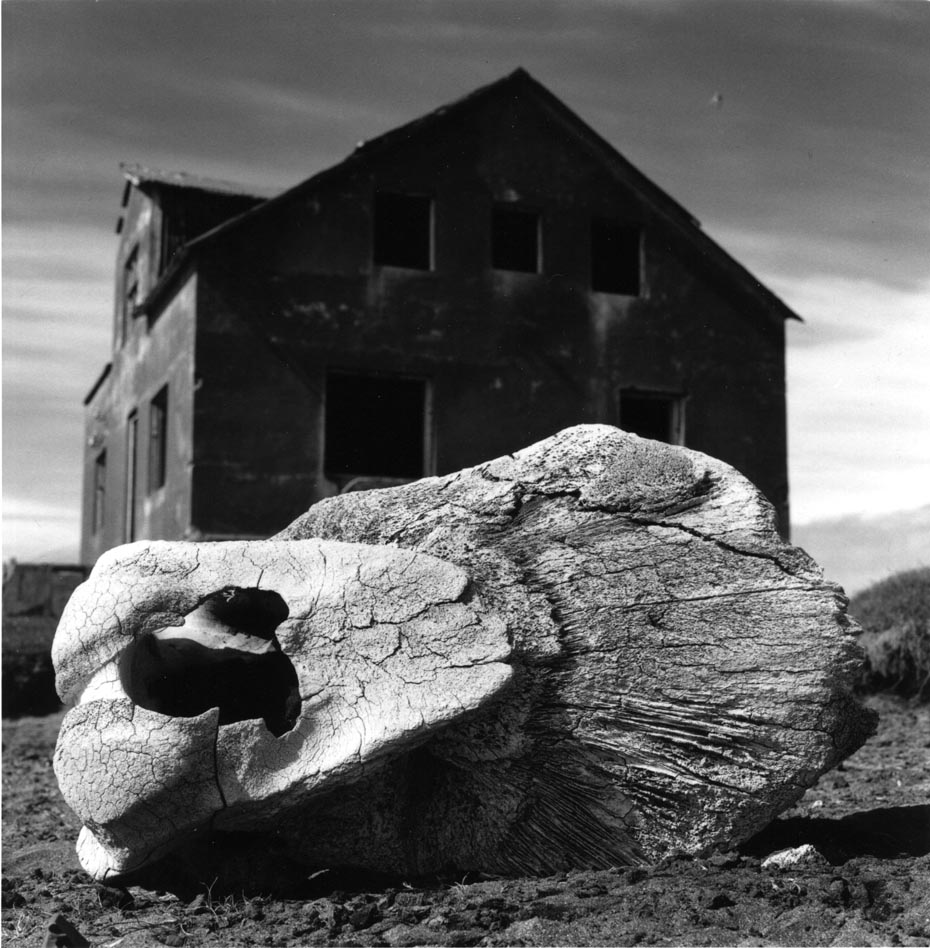

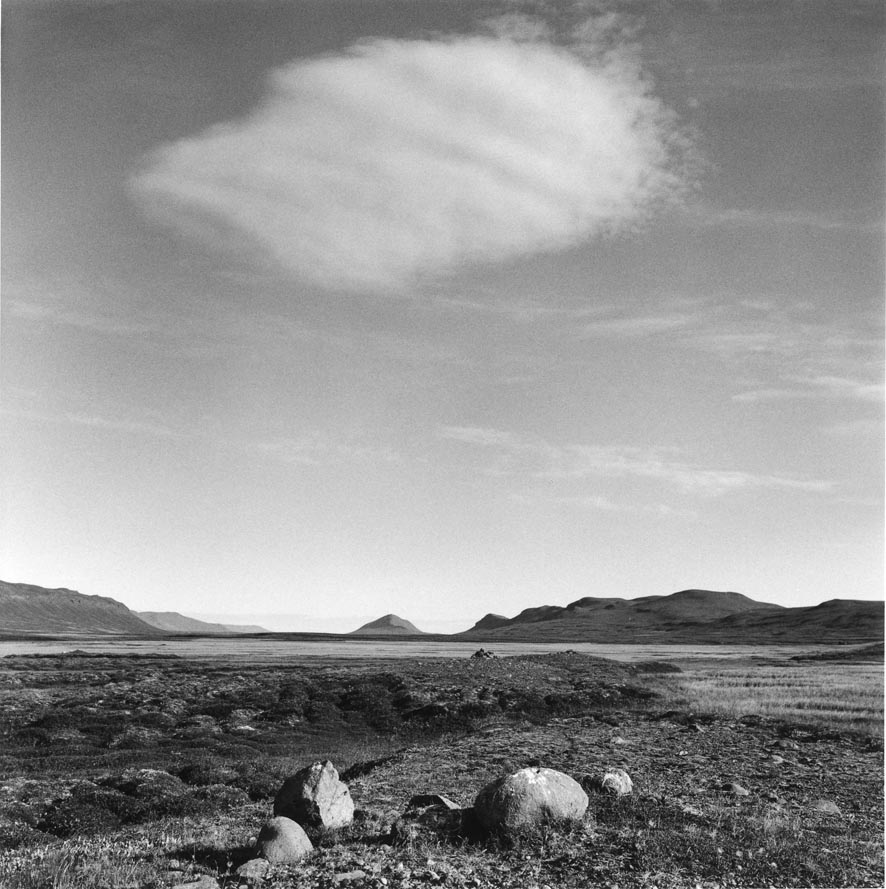

The series of photographs collected under the title of Steinholt – A Story of the Origin of Names, alludes to the fact that the names of older persons are handed down to the younger generations, so as to prolong the time in which the former are remembered. The photographer has here created his own personal fresco, which, although in some cases is intended to conjure up the past, even in detail, manages to go far beyond the sole evocation of bygone events. Even when they portray specific places and experiences, these images do not require any anecdotal explanations. The natural environment found in these areas, which are so ill-suited to sustain human life, possesses a beauty and pureness that are difficult to find in more hospitable settings, while human dwellings, be they ruins, or recently abandoned, make up for their meagre furnishings with breathtaking views from unhinged windows.

In the digital era of speedy, distracted communication, Christopher continues to use old, heavy analog cameras and the black-and-white roll film that he personally develops and prints. The months spent steeped in this island’s landscape, exposed to the wind and the elements, are followed by long days spent in his darkroom in the South of France, where he spends his time viewing and sealing his memories on paper, sustained by countless cups of strong tea. The photographer’s Icelandic summers, swathed in limitless light, are thus followed by long periods of self-imposed “darkness.” It is through this rigorous regime that his images are distilled, delivered as hymns to beauty in which the blacks and whites of endless hues manage to lend a higher, more ethereal quality to these snapshots of life Christopher has captured.

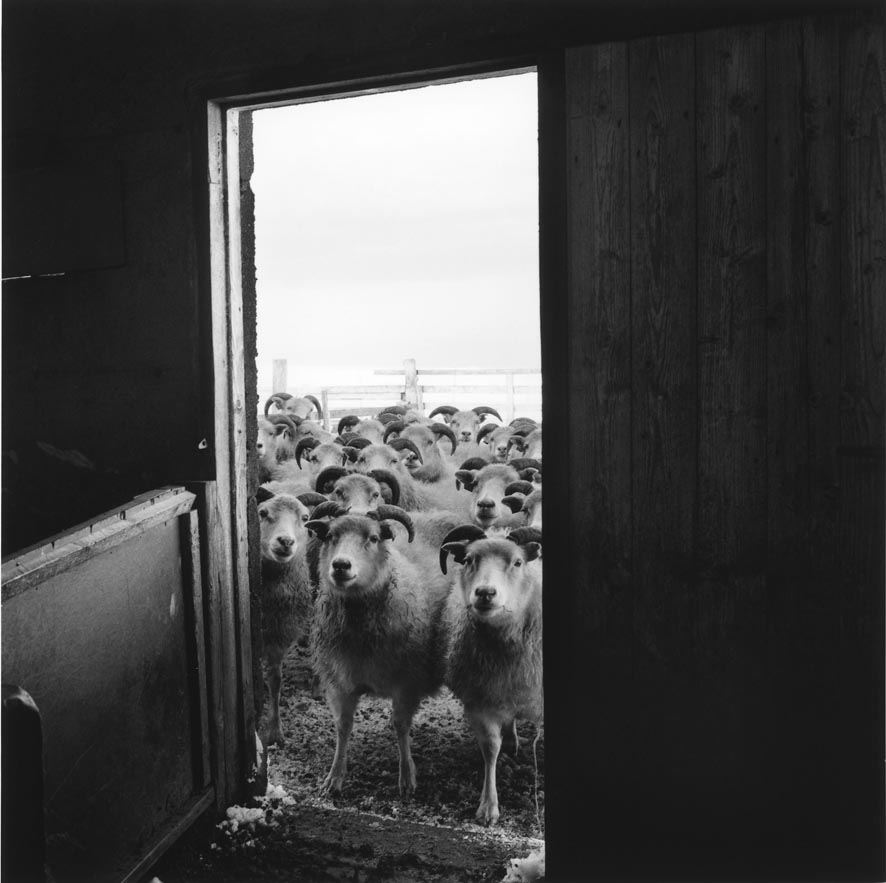

Landscapes, architecture or portions thereof, animals, and portraits – these are the themes of all three of his series devoted to Iceland, of which they convey quite a full picture. Although in India Christopher has very successfully tried his hand at portraying Kolkata and Mumbai, I am convinced that his preferred subjects are open, natural spaces. Here the eye may wander towards distant or nearby elements, focusing on commonplace details (a brooding duck, or a few rhubarb leaves) that he renders poetic and charged with significance, or on infinite horizons that are striking and sometimes frightening in all their primordial energy. Christopher loves freedom; he loves being able to disappear and not be found or even sought. This is a wish the Icelandic landscape has no trouble fulfilling, just as when, having waited several days for the weather to stabilize (at least for a little while), he leaves the house one morning, determined to push on as far as Heljardalur, located about 50 km from Thorshof. Known as “the valley of Hades,” it is the place where they say the old and infirm were once taken in the autumn, and Christopher knows he will have to face a tiring journey over treacherous terrain, with no trails and no reliable points of reference to guide him. He also knows he will have to make due and rely on his own wits when faced with whatever unexpected event he will come across. What’s more, the weather could have some surprise in store and he must be prepared to defend himself. In short, he tends to place himself under circumstances similar to those the inhabitants of this area encountered fifty or a hundred years ago; in a certain sense they are even more difficult since he was not even raised in this country.

Familiar Gazes

In comparison to the photos taken in China and India – the two countries he has visited most often besides Iceland – here it is the photographer’s personal life that is involved. While it is true that individual interpretation is always entailed in forming each image, these photographs are imbued with something more intimate because they evoke Alfheidur’s family history. Christopher delves into traces of the past and the surrounding environment in search of a key that will help him gain a greater understanding of the woman who has been his partner for over thirty years. In Iceland, he is not just an especially well informed, thorough traveler, but a man who wants to be part of what he sees and wants find out what it means. The way in which he expresses this sense of belonging is nonetheless only suggested: the autobiographical details are emblematic, and thus it is not so important if one of the crumbling farms is actually the one in which his wife’s ancestors lived because most Icelanders can pick out similar elements in the stories of his or her own family.

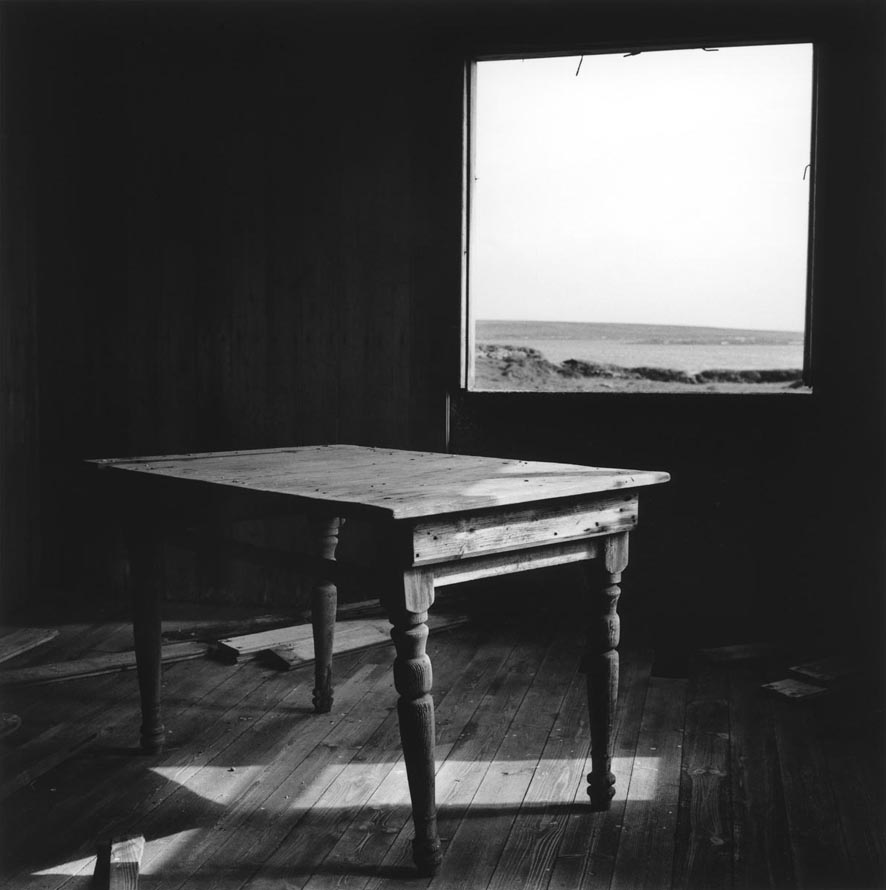

The portraits are of people who, besides living in Thorshofn or thereabouts, have (or had) some sort of relationship with Alfheidur’s family or with the photographer himself, who would run into them while going about his daily business, or on one of his hikes, and whom he recognized as personifying the very essence of the area’s inhabitants. They are men and women with whom Christopher spent hours or days, and with whom he shared meals and conversations, whom he observed in the hopes of seizing both their similarities and differences. One could say that they were posing, in the sense that they knew they were being photographed, but their gazes show that they did not change for the lens’s benefit. They retain an inner “integrity” that is sustained by a feeling that they are in tune with the image of themselves that the photographer will convey – it is a sign of great trust. More so than is the case with some other subjects (landscapes, architecture) he photographs, here we tend to ask ourselves who these people are. We imagine anecdotes and blood ties that often do exist, but, as can be said for all of Christopher’s images, these portraits seem animated by a life of their own that nurtures us, through their mute, yet intense, gazes alone. Perhaps the only truly “contrived” portrait that merits a brief explanation is that of his wife holding a mirror that belonged to her grandmother, Alfheidur (whose name the two women share). In the photograph, the granddaughter’s face is curiously only mirrored in part, as if to suggest that the contemporary Alfheidur only partially recognizes herself in the figure of her beloved, esteemed grandmother, given that life has led her faraway, where she was able to find unimagined and unimaginable possibilities.

Lines and Spaces

Ever since, over ten years ago, I began following Christopher’s work, I noticed his penchant for central, solid compositions with a preferably square format and often structured along straight lines. This last feature is more obvious when he photographs architecture, but a number of sharply delineated horizon lines in his numerous marine scenes also come to mind. The images he envisions are almost always symmetrical and aim for a harmony that renders them perfectly balanced. He possesses a great, innate talent for calibrating the elements within a photograph, which means that overly “full” or dark spaces are counterpointed by more luminous, empty ones that are not necessarily the same size, but which precisely contribute what it takes to create a visually balanced image. Sometimes they are but flashes of isolated light, yet so powerful and significant as to counterpoint even extensive dark areas. Many photographs display a skillful, organic combination of straight and softly curved lines, and it seems to me that Christopher’s eye does not mean to distinguish between what is “artificial,” in the sense of “manmade” and what is “natural.” On the contrary, I think he avails himself of those elements that characterize these places, where nature is endowed with such an untamed force as to swallow up all human artefacts (as opposed to the opposite tendency, which is the case almost everywhere else in the world). This makes us feel that even humankind and its products are wholly at one with nature. I’m not just referring to those images in which the human legacy is merely a vestige of the past and is fated to slowly disappear (Fragranes, Skinnalon, Rif & Whale, Tungasel, Assel), but also to those in which the human presence is still actively making an impact (Fontur, Saudanes church, Svalbard, Steinholt). Yet, it is a presence that takes account of, and is determined by, the context in which it is placed, thus showing a respect that I am sure the photographer admires and shares. Indeed, his is truly the wrenching, nostalgic hymn of one who considers a respectful exchange with the universe possible only when myriad human stratagems are unable to overcome the primordial power of nature itself.

Sky and Sea

The sea as Christopher photographs it makes us want to invent specific names for each of its individual “states,” just as the Inuit people employ various terms to refer to the snow in its many variations. There’s a flat seascape bathed by a luminous ray of slightly clouded sunlight: It opens our hearts and conveys a sense of boundless serenity (Solvanov). Another image shows a tongue of water as it sinuously or jaggedly slides into coves that are set off against a line of hills in the distance, and an overhanging sky that is so immense as to seem out of proportion with the rest of the scene (Langanes on the Horizon). Then there’s the sea darkened by a looming mass of clouds that appear so dangerously close to the photographer’s lens and the viewer as to spark the fear of being sucked up by its threatening force. A seagull hunting for fish hovers over an expanse of rough, leaden waves, conveying an unpleasant chill (Pistilfjordur). The sea is photographed from an intermediate position with respect to that of whoever is on the boat and a bird’s eye view: the water is choppy, but not threatening, while the sea is separated from the sky amid hazy layers of steam and the water is cut by a curious line formed by various merging currents (Sea Line). The more I observe them, the more I realize that, despite constituting an objective, macroscopic reality, these seascapes constitute the theme through which Christopher best expresses his state of mind, employing it as he sees fit and rendering it a docile, ductile conduit of himself.

The sky is just as immense and intense and it is sometimes contrasted with the expanses of land and sea in which it is mirrored (Naustinn, Langanes; Sandkrokur; Close to Haldorskot; The Way to Heljardalur). At other times, it becomes the sole protagonist, sheared by the free or coordinated flight of birds (Arctic Terns in Rif; Geese) and a symbol of an even greater, ineffable existence.

All the Rest

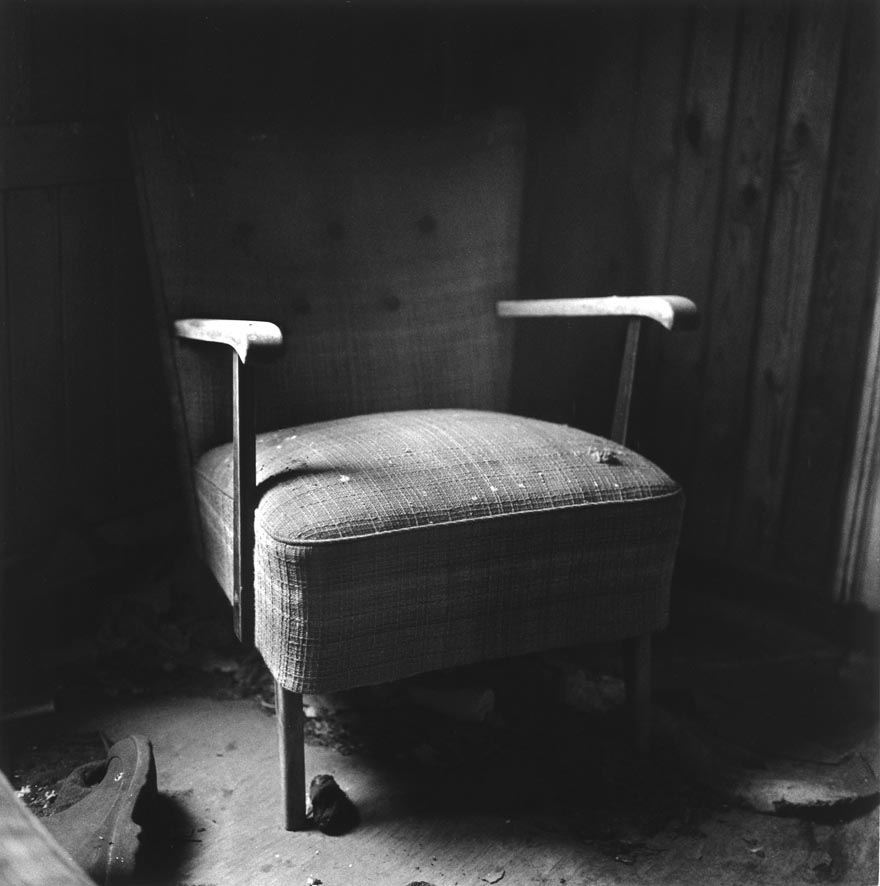

Beyond the photographs’ compositional harmony; their balanced light and dark areas; their interplay of straight, sharp lines and softly curved ones; and their thematic variety, there is one thing that strikes the viewer upon a closer look. That is that each image is the fruit of a single, fundamental quality: that of observing each aspect of the world with a careful, thoughtful, affectionate eye. In Christopher’s view, value is not attributed to something based on some hierarchical order: he captures the essence of each thing, person, animal, or landscape and considers it a living piece of the universe. There are no inferiority or superiority complexes, and not even an equality complex (as the Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh suggests) because the boundaries between one thing and another disappear, making the mineral, animal, and vegetable kingdoms all part of a single symphony. A simple sledge lying in the snow, a frosted glass cake dish, an old, dusty armchair, a guillemot’s egg – all of these shift us from the boundless realm of nature to the more intimate episodes of daily life, in which we may more sharply recognize the signs that mark the passage of time.

This is a notion that specifically distinguishes humankind and to which we perhaps owe our painful awareness of the finite. Christopher’s images and the timeless, suspended state they evoke help us to overcome that awareness, lifting us aloft towards vaster horizons.

Monica Dematté

Vigolo Vattaro, 2 March 2016

Translated by Francesca Giusti